Crystal

France may not have invented crystal, but it has become its best ambassador. Our artistry in this field, closely linked to our tableware tradition, is unique.

In France’s Grand Est region

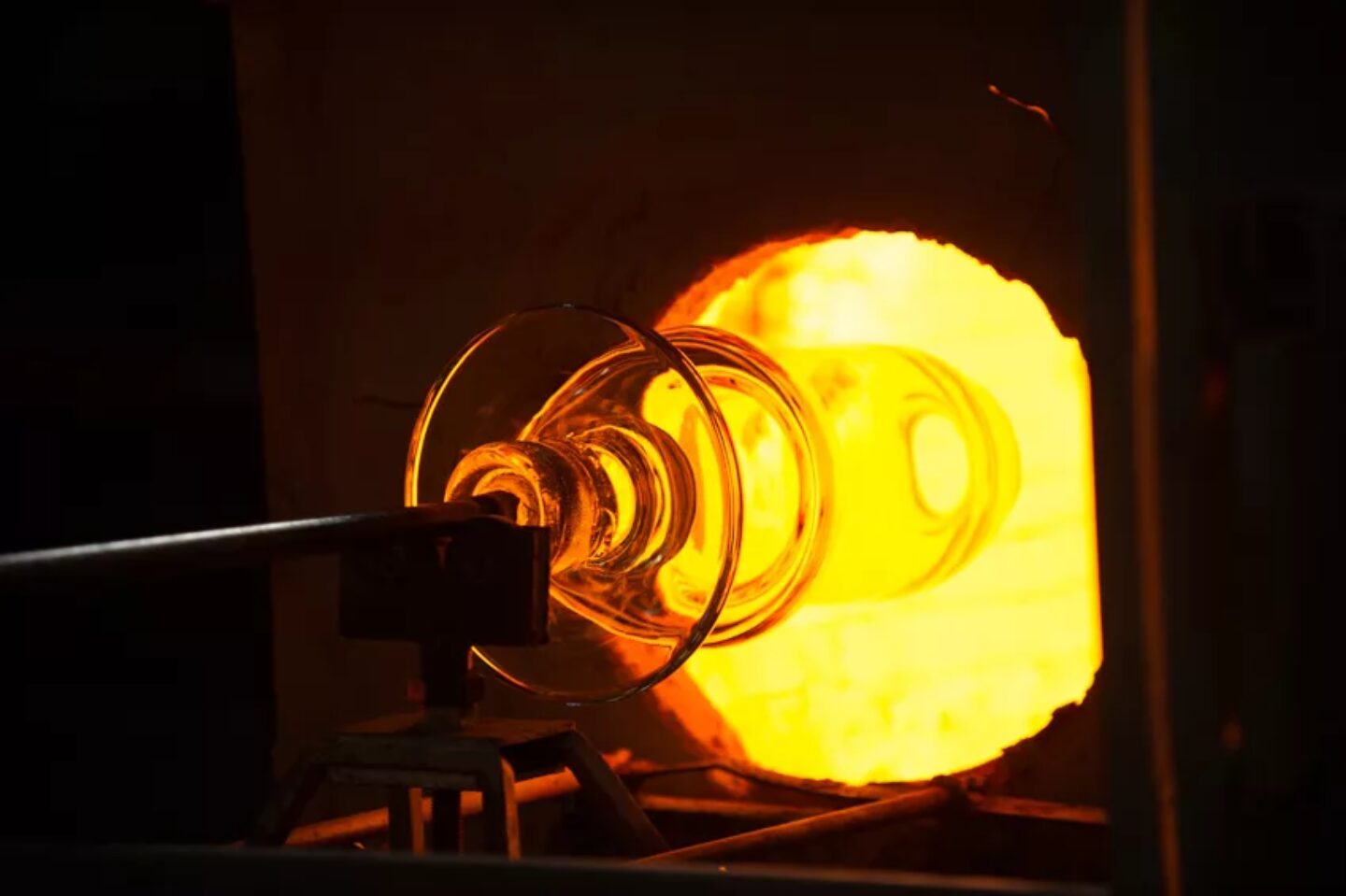

While crystal was discovered by chance by the English in the 17th century, it was in France that it gained prestige. Convinced by the then Bishop of Metz, Monseigneur Louis de Montmorency-Laval, of the necessity to build a glassworks in the kingdom, rather than importing crystal from Bohemia or England, Louis XV authorised the creation of large factories in eastern France. This region had access to all the necessary elements: wood, water, fern, lye, and, most importantly, lead, the material that makes crystal different to glass.

Dinner is served!

The 19th century was an era of great advancement with the first mechanised systems and mould-blowing. Research into colouring processes also proved successful, not forgetting the emergence of white and opal crystal.

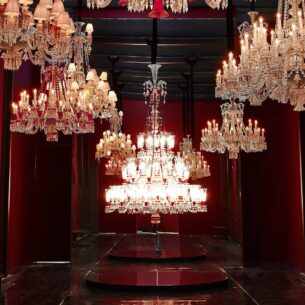

This particularly sparkly material (because of its high refractive index) became an essential item of tableware. The new bourgeoisie adopted the service à la russe manner of dining, whereby courses are brought to the table one after the other, and each guest would have an array of crystal glasses. They also replaced thousands of rock crystal drops and other chandelier accessories, which had become too expensive, with crystal.

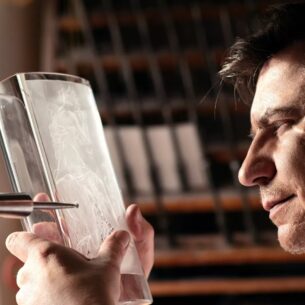

Art and crystal

French crystal reached the pinnacle of success in the 20th century, with the art nouveau and art deco artistic movements. The works of René Lalique and Emile Gallé, presented at the Paris World Expo, triggered a wave of enthusiasm. Crystal was blown or moulded, and then enhanced by a myriad of techniques such as marquetry and engraving, thus becoming a real means of expression in French art. And it has not left this pedestal since.